The trip to Big Mountain on the Navajo Indian Reservation in northern Arizona is a long one. No matter where you come from. You will cover more than miles on the red dirt roads of the high desert plateau. The winding, bumping hours you spend will take you from your comfort zone. It will feel like another time, one governed by the movement of heavenly bodies and seasons instead of blinking digital numerals.

The trip to Big Mountain on the Navajo Indian Reservation in northern Arizona is a long one. No matter where you come from. You will cover more than miles on the red dirt roads of the high desert plateau. The winding, bumping hours you spend will take you from your comfort zone. It will feel like another time, one governed by the movement of heavenly bodies and seasons instead of blinking digital numerals.

Here days are spent among people who have an understanding with their creator about the place where they live and how to care for it. And in that way care for themselves and others. A way of life know as The Beauty Way.

Traditional Dineh (Navajo is Spanish) people have the language, songs, ceremonies and culture from time immemorial. They are descendants of people who have lived in this area for thousands of years. They will tell you stories of the land, plants and animals. They can talk of special relationships with all of them.

The people of the Black Mesa and Big Mountain area can also tell you about ancestors who hid in the mountains during the time of the “Trail of Tears” marches to Oklahoma and back. People who never left the area. That spirit lives on in the resistance to forced relocation at the hands of the US government today. It’s more of the same old story these traditional people are facing.

It’s an ugly tale of greed and deceit. A tangled web of strip mines, multi-national corporations, environmental destruction and government corruption. The level of disrespect and intimidation brought to bear on the Dineh, combined with the spiritual degradation prompted an investigator from the United Nations to file a very critical report on human rights violations by the US government in 1999.

Through it all these powerful, beautiful, mostly elderly, traditional Dineh carry on a way of life that people dream about. Raising sheep, spinning, dyeing and weaving the wool into the ancient art that is yet so vibrant in the moment. Life in the hogan, with the door facing east. Corn pollen and sage bundles. Sundance and ancient prayers.

Native culture and wisdom is more sought after than ever. Indian art, literature, music and events are becoming mainstream. It’s ironic that the real keepers of this earth wisdom are being systematically removed from that life as a matter of government policy.

It’s a world that should be revered and honored for the national treasure it really is, instead of shoved out of the way as an inconvenience to a multi-national corporation trying to make money. It’s the third world within the first world. The extreme poverty of the “first Americans”, who have riches we don’t even know how to ask them about.

For the past ten years I’ve been involved in a cultural exchange with the Dineh resistors from this special world. There are many mediums of trade in this program, but music has been the centerpiece.

My brother Bear and I have been playing music together since childhood. He’s a singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist. I play drums, tell stories and try to sing a little. Since 1986 we have played with various members of our family and lots of friends in a group we call Clan Dyken. We have played thousands of shows all over the US and the world, met people from many nations and cultures and been profoundly influenced by these experiences.

The music we make continues to evolve from its rock and roll roots, passing through world beat, folk, and back to basic acoustic. You might see Clan Dyken rock out at high volume on a festival stage with a full electric band playing to a crowd of thousands or in a small circle with a big drum beside the fire on a moonlit midnight deep in the woods.

Over the years we have built what some people call a cult following. That’s code in the music business for a small, but dedicated fan base. We have self-produced and released eight recordings, sold a few thousand, given away nearly as many and continue to work on new songs.

Through all the miles and songs our trips to Big Mountain have been some of the most memorable. The people have impacted our lives and music. The 1999 Clan Dyken album Revive the Beauty Way features a Traditional Dineh dwelling, known as a hogan, on the cover and songs that tell stories from our trips to Big Mountain and Black Mesa.

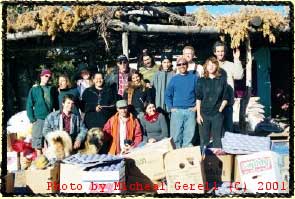

With the help of manager Michael Gerrel we have organized a food and supply run to Big Mountain every year since 1994. The efforts of a great number of people have made it possible to deliver tons of food, building supplies and clothes to the traditional resistors of forced relocation. We also provide labor for woodcutting, sheep herding and household repairs.

The trip is supported by a series of benefit shows in the preceding fall months. From September through early November food, supplies and funds are collected for delivery to homes on the reservation. Concerts are organized by local supporters in small towns throughout Northern California and Southern Oregon. Places like Murphys, Arcata, Hayfork, Takilma, Ashland and Sonoma. Residents of Big Mountain often travel with the band, speaking to audiences about their life on the reservation. Every stop on the tour has a special flavor, with contributions from the area added to the traveling show.

The trip is supported by a series of benefit shows in the preceding fall months. From September through early November food, supplies and funds are collected for delivery to homes on the reservation. Concerts are organized by local supporters in small towns throughout Northern California and Southern Oregon. Places like Murphys, Arcata, Hayfork, Takilma, Ashland and Sonoma. Residents of Big Mountain often travel with the band, speaking to audiences about their life on the reservation. Every stop on the tour has a special flavor, with contributions from the area added to the traveling show.

Local bands, dancers and speakers mix with the Clan Dyken music and drumming.

Each year is a new adventure. A grass roots people to people outreach and exchange. At the concerts we invite the hardy and willing to make the trip to the reservation with us. They see first hand what like it’s like when you are the target of corporations and the US government. Every year the people who make the trip for the first time are amazed and awed.

Amazed at what is being done to the people of Big Mountain/Black Mesa in this day and age, by a government that points fingers around the globe at other countries for human rights abuses. Awed by the beauty and power of a life that has a connection to the real world in a way that most of us moderns have trouble grasping.

During this time we have developed a closeness with the people. They have honored us by extending invitations to ceremonies, sharing meals and stories and always asking us back.

I have sat in wonder as grandmothers tell stories about their lives as young women. Sometimes I miss part of the story because I forget to listen to the interpreter. Grandmothers voice, even though it’s speaking in a tongue I don’t understand, gives me a special feeling. She is speaking of the fire and how her grandmother told her to keep it burning always, for her relatives live in that fire. I watch the flames dance among the logs in her dilapidated wood stove while the music of her language entwines with the high desert wind blowing the sand up against the hogan and get a sense of what she means without understanding the words.

Yes we are all like that fire. Here only in this moment, yet connected to every previous flame. Her ancestors, my ancestors and all the ones gone before have become fuel for that fire and will soon be ashes waiting to return to the earth and start over again.

Grandmothers are keepers of the sacred fire. They will share this wisdom if the world will listen. They are watching their culture die and I can see it in their faces. Faces that remind me of the desert with eyes that shine out like stars in the early morning on Black Mesa.

They have seen the bones of their ancestors scraped from the ground by the blades of bulldozers as they tear up the land in advance of the worlds’ largest strip mine for coal. They have seen the sheep die en masse with tumors from drinking contaminated water.

They know what it’s like to have their ever shrinking livestock herds rounded up and confiscated for “overgrazing”, only to be sold back to them. They watched the sacred Sundance grounds and arbor fall before the bulldozer, the blessed Tree of Life carved up with chainsaws. They have seen the wells dry up as water is sucked from the ground to slurry the coal on its way to the giant furnaces that foul the air with toxic black smoke. Furnaces that burn the earth to provide power to people in far away places like Las Vegas and Los Angeles. Even as the towers that hold the lines to carry the power criss-cross the reservation and hum with the crackle of electricity, grandmother often sits in the dark and cold with no wood to burn or candle to light. It’s illegal to gather firewood under the laws of relocation.

They tell stories that make me cry. They also serve fry bread that makes me laugh. They are gracious and powerful, yet vulnerable. They are facing a loss so grave there are no words for it in their language. To relocate or move from the land is to disappear. Every US presidential administration since Richard Nixon has set a deadline for their removal, but they remain. They have been bribed, coerced, threatened and tricked. Brute force and intimidation, false sweetness and cooperation, every tactic possible has failed to remove the hardiest of them. I know the world is a better place and we all benefit when these people are living the Beauty Way.

They are always gracious when we arrive. We usually set up base camp deep in the reservation on a part of the Benally family compound known as Anna Mae Camp. Anna Mae Aquash was an American Indian activist who died under suspicious circumstances in the 1970s. The camp is set in the high multi colored desert at about 6000 feet above sea level, surrounded by juniper, sage and pinon with a beautiful view of the San Francisco peaks rising over Flagstaff to the south west. This windblown homestead has been the sight for the Sundance ceremony and other gatherings for many years. The Sundance arbor and grounds were attacked and destroyed by agents of the Hopi Tribal Government and the Bureau of Indian Affairs last August as part of the ongoing war of intimidation. The camp has seen its share of confrontations and trouble, but it has always been a peaceful, welcoming place when the caravan arrives.

Louise Benally lives in the large hogan near the Sundance arbor. A single mother with four children, she has grown up in the resistance movement. When she was only twelve her elders instructed her to learn to speak English, so they could deal with the outside world. Since that time she has traveled around the world speaking (in English) about what her people are facing. She attends meetings, hearings, court battles, conferences and public gatherings of all sorts. She has a heart that’s bigger than the land she works so hard to preserve. A woman who stands in two places; she is savvy and articulate in the white world, but at home with the natural world of her people. Louise is our host and one of our guides to the even more remote and isolated homesteads on the reservation.

After a round of hugs and animated greetings the work begins. Crews are put together for the different jobs and the place jumps to life. Thousands of pounds of food, clothes and supplies are unloaded and divided for delivery. Wood is gathered and fires for cooking are started. Families who live close enough and have transportation start showing up shortly after we pull in. Grandmothers with jewelry and weavings will come by to show their wares, share some food and talk with Louise. Families stop by and soon children are running around the camp and balls are flying through the air over the sound of laughter.

After the goods are divided, trucks are loaded for the trips to homesteads. This is one of the most enjoyable and intense parts of the job. To drive for hours down rutted, sometimes wet and slippery, sometimes dry and dusty roads to arrive at a hogan that looks like it would have two hundred years ago and meet a timeless couple who are happy to see you is a special feeling that can only be found here. Even though they don’t speak English they make you feel welcome. The boxes of food, tools or clothes seem so small, yet Grandmother and Grandfather thank you with great sincerity. The gift of the life they lead seems so much greater than the few items we can deliver. But there is an exchange and we are all grateful to be a part of it. Grandmother is happy to know people remember and are thinking of her family. It’s a real life lesson to see people actually live off the land. No electricity, no phone, no TV, no computer, no VCR, just the real life. They don’t need all the things their home is being sacrificed for. They live with the land, animals, plants, weather, mountains and water. I’m happy just to see them. I could listen to the stories for days, but there is always another family to visit. It’s down the long road for another delivery and then back to camp for another load.

When the light fades the trucks straggle back to camp. The crew gets together for a meal. On warm nights we stay outside around the fire with the drums, guitars and voices. On cold nights we gather in the hogan and keep our spirits warm with stories and song while the wood stove warms our bodies. There have been long nights listen to Louise sing, trading stories and recounting the days events. Finally we fade off to sleep. Perhaps it’s the shape of the hogan or maybe the land it’s built on, but my dreams are always intense when I sleep there.

The sun rises through the cracks in the hogan door, which always faces east. I like to get up and start a fire before the rest of camp starts stirring. Mornings in November on the reservation can bring you many surprises. The red streaks of dawn may reflect off the new fallen snow or shoot across high clouds in a bright blue sky. There may be frozen drinking water and frost on the cars and trucks or a massive thunderstorm bearing down on the mesas across the canyon as a warm, moist wind blows into camp. I enjoy being there early and alone for a few minutes to get ready for another busy day.

The days fly by in a flurry of activity. Wood cutting, home repair, food delivery and sheep herding. One of the truly amazing aspects of the trip is how all the people rise to the occasion. There is something about performing a true service that lifts people up. Time and again I have seen the best side of people come out when they have the chance to really help make the world a better place. It’s a loaves and fishes effect, especially where labor is concerned. The work just keeps getting done. Thanksgiving day rolls around and all the deliveries are just about complete. Food to 200 families for the winter. We spend the day getting to the last homesteads, feasting and celebrating.

All too soon it’s time to go home. This place that once seemed foreign and remote has become familiar and comfortable. The trip back to another reality seems even farther than the one to get here. It will take a while for re-entry. The artificial colors of the chain store signs, the bright lights of 24 hour convenience stores, the hard smooth pavement, the chatter of radio and television, the speed of cars and pace of life all seem out of balance now. No matter where the traveler goes from here it’s a long way. The comfort zone doesn’t seem to fit so well anymore. Perhaps it should be left behind more often.